This is what The Santa Fe Indian School looks like now.

Unspoken: America's Native American Boarding Schools (Part Two)

Reforms In The Civil Rights Era

The next step forward in reforms came during the 1960s and 1970s, a period of American history marked by civil rights movements initiated by diverse groups of Americans.

American Indians were active in bringing awareness to their issues and gaining political capital. Political activism came in the form of the occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 and Wounded Knee in 1973. The American Indian Movement, a social justice group for Native Americans, was formed in 1968, the same year that Congress passed the Indian Civil Rights Act.

In 1969, Senator Edward Kennedy published the U.S. Senate report titled Indian Education: A National Tragedy—A National Challenge, which stated “The development of effective educational programs for Indian children must become a high priority objective for the Federal Government.” The report recommended more funding, moving toward bilingual programs, and elevating nutrition programs at schools that were predominantly attended by Native Americans.

In 1966 the Rough Rock Demonstration School was the first general education school to be opened by the Bureau of Indian Affairs on reservation land. In 1975, as a follow up to the Indian Civil Rights Act and the success of Rough Rock, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act was passed, allowing tribes to contract directly with the BIA for school funding.

Attendance in Decline

The number of boarding schools declined during this time. Some Native American parents saw the schools as a chance to have their children in an environment that wasn’t as impoverished as the reservations. The intermingling of Native Americans from different tribes was also seen as beneficial.

“The best thing about boarding schools is that it enabled our kids to develop relationships not only within our tribe, but inter-tribally,” says Forrest Cuch. “It created an intertribal Pan-Indian relationship across our country, enabled our people to relate to one another, and strengthened our political relationship nationally. We have one of the strongest, oldest organizations in the country called the National Congress of American Indians, and it's done a lot of good work. A lot of that came about because of the boarding school intertribal relationship that developed from those schools.”

The Santa Fe Indian School was undergoing major changes during this time. In 1962, the Bureau of Indian Affairs closed the school, and pushed students toward the Indian boarding school in Albuquerque. Studies showed that in 1975, 75% of the student population at the Albuquerque Indian School had been expelled, half the students were below grade level in reading, three quarters below grade level in math, and eleven out of 30 teaching positions were vacant.

The All Indian Pueblo Council formed a constitution in 1965, giving itself the ability to negotiate directly for grants directly with the BIA, private corporations, and individuals. In essence, the council gained local control to take on the issues they felt were most important.

Taking Control

In 1970 Delfin Lovato, a former Santa Fe student, was elected to the council. He immediately addressed the Pueblo Indians core problems: health, poverty, and education. The council took on the Albuquerque Indian School, signing a contract with the BIA which allowed them to hire a superintendent. The council picked Joseph Abeyta, a teacher and administrator on the Navajo reservation since 1965. With the support of the council, Abeyta and Lovato made the Albuquerque Indian School the first school to be administered outside of the BIA. Within a short time, they turned the school around.

During the renaissance of the Albuquerque Indian School, the All Indian Pueblo Council began looking at the Santa Fe campus. Many council members had been students there, and they felt it was the true school of the Pueblos. With the Albuquerque campus in disrepair (the Albuquerque Fire Department spoke of code violations), and with declining enrollments at the Art Institute, the council pushed to relocate the student population from Albuquerque to Santa Fe.

Abeyta explained: “From my humble standpoint, that school really belongs to the Pueblos. It was originally established to serve the area tribes, but the BIA, without any consultation, chose to establish a high school with an emphasis on art, and later changed it to an art institute."

Ultimately, the council proved victorious. Albuquerque Indian School was closed, the student population was moved to Santa Fe Indian School, and the American Indian Art Institute moved to a neighboring campus. In 1979 grades 10-12 transferred from Albuquerque Indian School to Santa Fe, and in 1981 a total of 450 students moved back to the school.

Rising Above

Many of the old boarding schools are now relics of history. Carlisle, the most famous, is a National Historic Landmark. Tomah Indian School in Tomah, Wisconsin, is a Veterans Administration Hospital. The Intermountain Indian School in Brigham City, Utah, closed its doors in 1984 and has since been demolished.

But some boarding schools have survived and evolved. The Haskell Indian School in Lawrence, Kansas is now Haskell Indian Nations University, billing itself as the premiere tribal university in the U.S. Sherman Indian High School in Riverside maintains a military-like boarding-school schedule, but has moved away from the assimilation concept. It teaches native languages and offers college prep and career pathway programs. And then there is the Santa Fe Indian School.

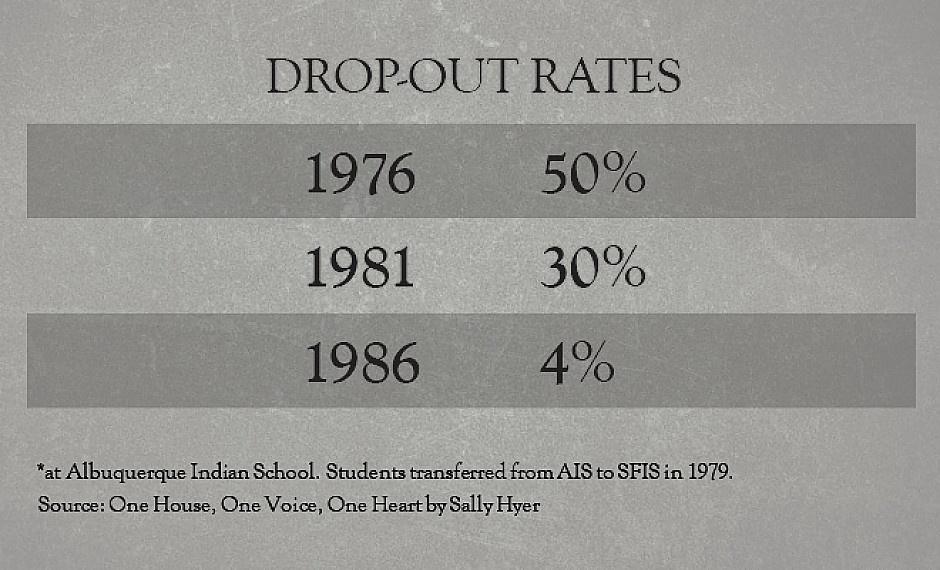

Academic standards at the school exceed New Mexico’s standards. It offers advanced college preparatory classes, tracks in computer programming, math and science, as well as a language arts program. It also has courses in Native American history and silversmithing. Since the council took over, the drop-out rate declined from 30% in 1981 to 4% in 1986.

Alicea Olascoaga is a recent graduate of the school, now attending Dartmouth College. She has strong memories of the Santa Fe Indian School.

“It’s the best that I’ve ever experienced and I think the best that New Mexico has to offer,” she says. “I’ve been in public schools in Albuquerque and I never had the same connection that I do with my teachers here. I never got the attention and the assistance that I have here.”

Alicia is also reflective when it comes to the history of her school, and the policy that created it.

“It’s definitely hard to think about boarding schools, the pain and anguish that Native Americans were put through during that time. But I think today it’s very different, and the purpose is to nurture Native Americans, and to ultimately benefit and to support and to improve who we are as a people as a whole.”