Unspoken: America's Native American Boarding Schools (Part One)

Origin Of The Boarding Schools | Assimilation Versus Extermination

The history of the United States of America is like a coin. For every story written of the successes and growth of the country, there is the other side — where people are subjected to the consequences of decisions over which they had no control. During the westward expansion of the U.S., the indigenous people were those people, whose treatment ranged from being dismissed to outright extermination.

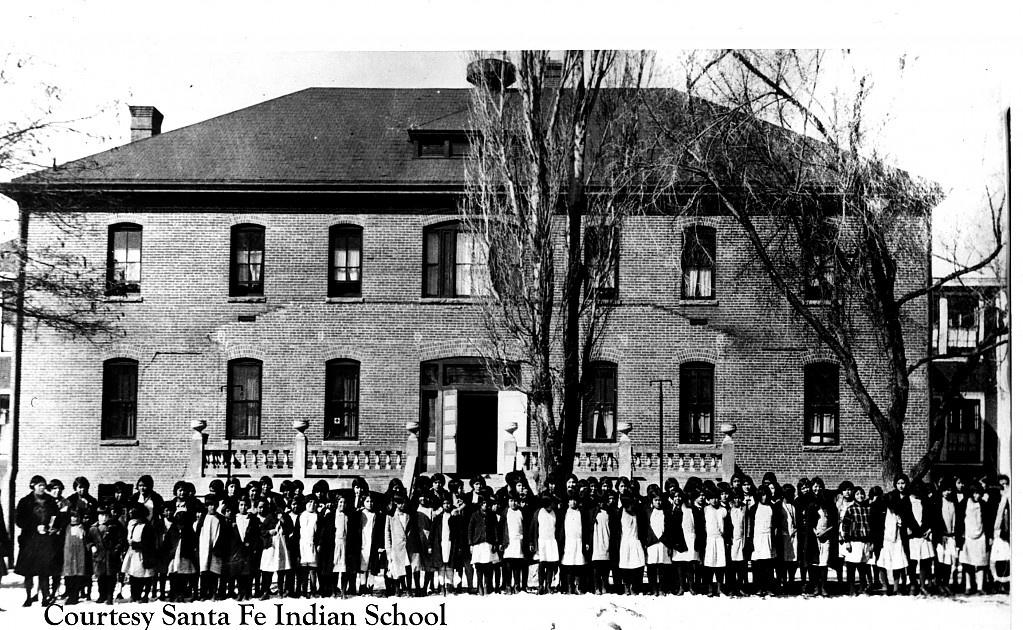

Somewhere along that spectrum is the story of American Indian Boarding Schools. One school in particular, the Santa Fe Indian School, today serves as a microcosm of American Indian education and the history of tribal culture since before the Civil War. The school also shows a potential path forward from a troubled past.

The boarding school concept can be traced to Civil War Army Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt, who led a unit of Buffalo Soldiers near Oklahoma. Together they captured 72 men from the Caddo, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa Nations, and transported them to Fort Marion, Florida. Upon arrival, the captives were forced to cut their hair, dress in military uniforms, and learn English. In essence, they were being groomed to resemble their white captors in an effort to “civilize” them. During a time in U.S. history when the policy toward Native Americans was usually one of forced removal and even extermination, the idea of assimilation, was considered progressive. The famous quote “Kill the Indian, save the Man,” is attributed to Pratt.

“I think that was a time when the government really felt like they could deal with the so-called ‘Indian problem,’" says Amanda Blackhorse, a Navajo who is a social worker from Arizona. “And it was the last option to go for the children.”

“Early assimilation policies were to steal Native American land,” says Christy Abeyta, Superintendent at the Santa Fe Indian School. “If we can assimilate these Native Americans into the dominant culture then they have no need for reservations, they’re going to migrate into urban areas and there will be no need to maintain tribal lands, because they would have lost their culture, the language, all ties to what they held so sacred…and that was the land.”

The policy of assimilation reached a low point with The Dawes Act of 1887. Reservation land was distributed to individual families from the communal tribe or nation in an attempt to force Indians to farm, and to model the western family land ideal. By 1900 Indians had lost 60 million acres of reservation land. The Dawes Act was one of many official processes put into place to “kill the Indian, save the Man.”

Christy Abeyta talks about the importance of preserving traditions.

"Early assimilation policies were to steal Native American land."

Christy Abeyta, Superintendent at Santa Fe Indian School

The Carlisle School

Carlisle Indian School; Carlisle, Pennsylvania

After his experience assimilating the prisoners at Ft. Marion, Pratt came up with the idea of immersing Native American children in white culture through boarding schools. He convinced several tribal leaders on reservations and in Ft. Marion to send their children with him, arguing that if they were to learn English they could read and understand the treaties signed between governments. In 1879, the first class of 147 children, many of them children of tribal chiefs, traveled to Pennsylvania to the newly created Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

Haskell Institute; Lawrence, Kansas (1913)

Library of Congress

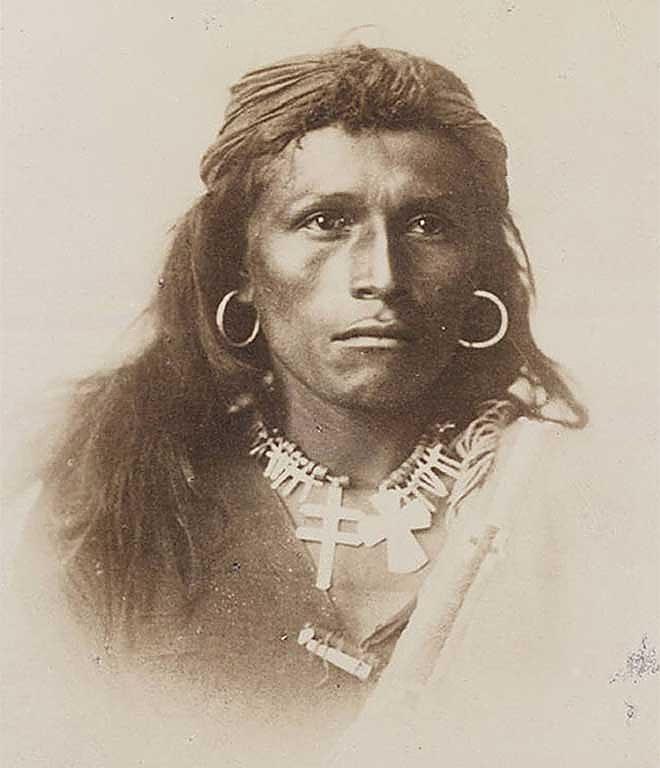

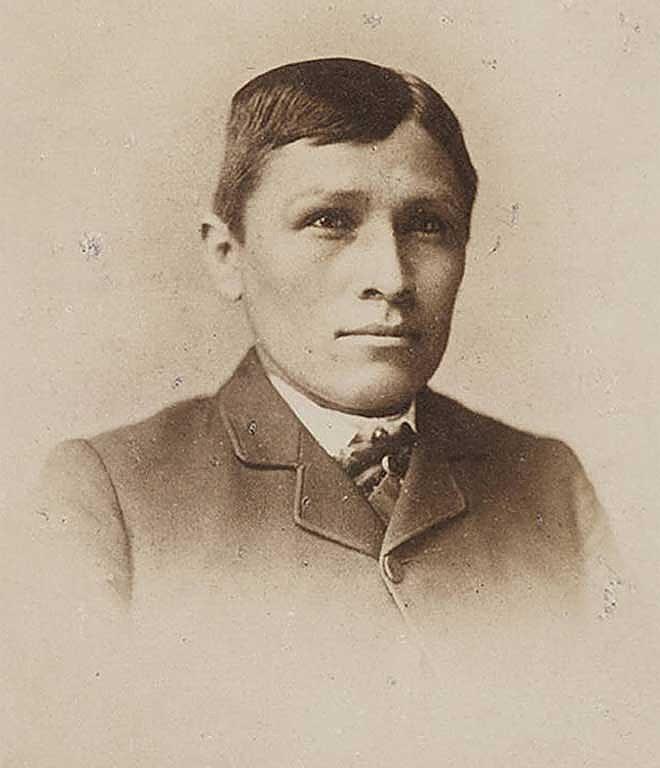

Assimilation practices began immediately. Children were separated from siblings. Hair was cut. Uniforms were distributed. No traditional dress was allowed. The students marched to class in the mornings, and had trades training in the afternoons. Students were forced to learn and speak English; their native languages were to be unspoken.

In 1890, ten years after the creation of the Carlisle schools, the Santa Fe Indian School was founded. It became one of many boarding schools, including the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon; the Pueblo Indian School in Pueblo, Colorado; and the Haskell Indian School in Lawrence, Kansas. All of them followed the Carlisle model of trying to eliminate all native culture and influence.

Before

Navajo Tom Torlino, 1882

After

Navajo Tom Torlino, 1882

Students were forced to learn and speak English; their native languages were to be unspoken.

Life For The Students

In Sally Hyer’s book, One House, One Voice, One Heart: Native American Education at the Santa Fe Indian School, many turn-of-the-century students at the Santa Fe school recount being frightened overwhelmed by their experiences. Children from different tribes could only communicate to each other through English, reinforcing the elimination of native languages. But there are also accounts of positive aspects. Some students appreciated the running water and having new shoes. But even these benefits had drawbacks. A teacher at the time felt that it was “the policy of the Indian Office to buy the very cheapest” shoes.

Students talked about their loneliness, about being away from their families. Some would try to run away, only to be caught and brought back. They talked about not having enough to eat, military drills, and marching in uniform. These anecdotal stories tell the greater story of losing the culture they once knew. The results of the assimilation practices in all boarding schools were long lasting.

“It was very destructive,” says Forrest Cuch, owner of Full Circle American Indian Consulting and the former director of Indian Affairs for the state of Utah. “It caused historic trauma among most of our people, including myself, to this day. It was so ineffective that it did not train us to become confident in the white world, and it took us away from our own culture, so much so that we weren't even competent as Indians anymore.”

“Many of our people are suffering, and they don’t realize that they are suffering from the boarding school syndrome,” says Amanda Blackhorse. “Many of us don’t even understand it, in that perspective. The effects of it are very real and people feel them all the time today, and I think that’s a sign that we haven’t really dealt with it as indigenous people.”

End Of The Progressive Era

The years during the existence of the Carlisle Indian School, known as the Progressive Era, were tumultuous ones for the United States. The country saw an explosion of social welfare laws. Women’s suffrage, prohibition, child labor, and health reforms on businesses were all part of the public discourse. Immigration reform and restriction were volatile issues, with the demand for “Americanization” of all immigrants.

In this environment, Pratt’s view on assimilation of the American Indians was debated against the reservation system, and the idea of a “civilized” Indian was, in his mind, much better than the popular portrayal of an American Indian as a savage in a Wild West show.

“I try to be very unbiased when I teach my students about assimilation and about Indian removal and the reservation era,” Abeyta says. “It’s not true for all Americans or westerners that the intent of Native American policy was to obliterate all natives. There were some very caring and compassionate people during that time that advocated for Native Americans and philanthropists that worked to help Native Americans during that era.”

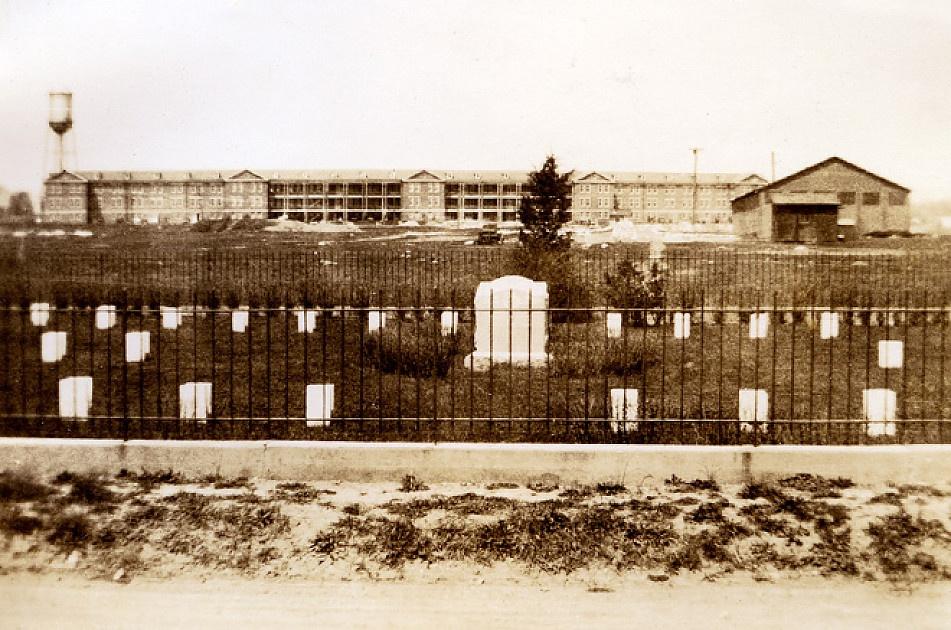

The Indian Boarding School system would stay in place for decades, even after the closing of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in 1918. The school’s buildings were converted into a World War One convalescence hospital. A cemetery remains on the property, a grim reminder of 180 children who died while attending the school far from home.

Stealing Land Again

Toward the end of the Progressive Era the policies affecting the First Nation peoples were being reevaluated. In 1922, Senator Holm Bursum of New Mexico proposed S.R. 2274, known more commonly as the Bursum Bill. It effectively legalized all land claims for land that was originally occupied by the Pueblo tribes when New Mexico became a state. The bill passed the Senate without public discussion, but the House of Representatives demanded hearings.

These hearings opened one of the first modern opportunities for Native Americans to have a voice in what had happened to them. The Pueblo people of New Mexico reconvened the All-Pueblo Indian Council, an inter-tribal group formed in 1592 but not active since 1680. Arguing on their behalf was John Collier, a sociologist who felt that traditional cultures — immigrant and native — were important to the national identity. The Bursum Bill was overturned with the passing of the Pueblo Lands Act. Later, both the All-Pueblo Indian Council and Collier would move the conversation of Indian rights forward.

A New Deal

In 1928 the Brookings Institution released a report titled “The Problem of Indian Administration,” which came to known as the Meriam Report. In it, investigators recommended teaching skills that would benefit both the native cultures and American society, discontinuing the European-American-centric cultural courses, and bringing schools closer to the homes of indigenous people. The Meriam Report factored into a larger piece of legislation that came from newly-elected U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt — the New Deal.

The Great Depression forced the U.S. government to create jobs and provide services for a country in need. Roosevelt enacted numerous policies and work programs, including the Social Security Act and the WPA. Based on the Meriam Report, Roosevelt created the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, also known as the Indian New Deal. Its primary goal was to give the tribes more opportunity for self-determination and self-governance. It also addressed the loss of reservation land, reinforced sovereignty of the different nations across the country, and created a priority hiring system in the Commission of Indian Affairs.

Roosevelt appointed John Collier to head the Commission of Indian affairs. Collier demanded the closure of several national and distant boarding schools, and the opening of more regional schools, which began a trend of increasing the number of students at boarding schools. However, these new schools still had many of the same problems as the earlier schools.

“Tuba City Boarding School. That was the worse I went to,” says Roy Smith, a Navajo born in 1950 who went to several boarding schools beginning in 1959. “If you get caught talking Navajo to another student, your name is on the list. And the way they used to do it was they'd get a bar of soap, and they'd shave it off with the pocketknife, and then they mix it with water. Then that's what you use to rinse your mouth. Don't ever use another word of Navajo.”

In 1948, Bushnell Hospital in Brigham City, UT, was converted into the Intermountain Indian School, and in 1950, 500 Navajo students moved into the newly-created barracks. The coursework was mainly vocational, but as in most other boarding schools, English was forced upon the students, and Navajo was forbidden.

Santa Fe Indian School, 1932-1962

"The way they used to do it was they'd get a bar of soap, and they'd shave it off with the pocketknife, and then they mix it with water. Then that's what you use to rinse your mouth. Don't ever use another word of Navajo."

Roby Smith, student at Tuba City Boarding School

“Tuba City Boarding School. That was the worse I went to,” says Roy Smith, a Navajo born in 1950 who went to several boarding schools beginning in 1959. “If you get caught talking Navajo to another student, your name is on the list. And the way they used to do it was they'd get a bar of soap, and they'd shave it off with the pocketknife, and then they mix it with water. Then that's what you use to rinse your mouth. Don't ever use another word of Navajo.”

In 1948, Bushnell Hospital in Brigham City, UT, was converted into the Intermountain Indian School, and in 1950, 500 Navajo students moved into the newly-created barracks. The coursework was mainly vocational, but as in most other boarding schools, English was forced upon the students, and Navajo was forbidden.

The Santa Fe Indian School was also going through changes during this time. In the 1920s, the school started to focus on traditional arts, and in 1934 Dorothy Dunn opened a studio school on campus. Numerous famous artists came from this school, and they helped define an artistic look that was associated with Santa Fe. More notably, her classes broke from the regimented teaching style that suppressed indigenous culture and instead allowed for celebration of the students’ heritage. Although she only taught for five years, the studio school continued until 1962 under the leadership of Geronima Cruz Montoya.

But, all the advances made by Collier beginning in the mid 1930s were being chipped away. The ideals of strengthening tribal governance gave way to a new attitude of integration. Collier resigned from his post in 1945 due to lack of congressional support. While 60% of the staff of the Santa Fe Indian School consisted of Native Americans, the federal government pushed the responsibility of education away from the tribes and toward the states.

The Santa Fe Indian School was still a boarding school. In addition to the art classes, manual labor and trades were a primary focus of education. Much of the students’ time was spent on maintaining the schools, mending their own shoes and clothing, even firing up the boilers at 5:30 AM for heat.

Utah Historical Society

Utah State Historical Society

Utah Historical Society