What does fungal health look like in the garden?

Most problems that we see in the garden are a result of poor soil health.

Signs of poor soil health include:

- yellowing of plants (indicating the plant’s inability to receive nutrients)

- browning of leaves (fertilizer damage)

- excessive pests (poor endophytic and mycorrhizal health)

- compacted soil (lack of beneficial soil microbes)

- excessive weeds (lack of soil fungi)

Healthy soil is alive, and the soil biology is what produces healthy plants. As a rule of thumb, we want to facilitate the health of saprophytic, endophytic, and mycorrhizal fungi. When these populations are healthy, there is not as much opportunity for parasitic fungi.

Mushrooms that pop up in our garden are usually mycorrhizal or saprophytic. These are typically beneficial, along with the many other mycorrhizal and endophytic fungi that we can not see. Visible fungal infections on our plants (as opposed to on decaying matter or attached to plant roots) can be an indication of a parasitic fungus (think mildews and blights).

Learn more about healthy soil with local soil expert Paul Grossl here!

What agricultural practices harm fungi?

Unfortunately, many of the practices used in industrial agriculture and even some of the methods we use on small farms or home gardens can be detrimental to fungal health and diversity.

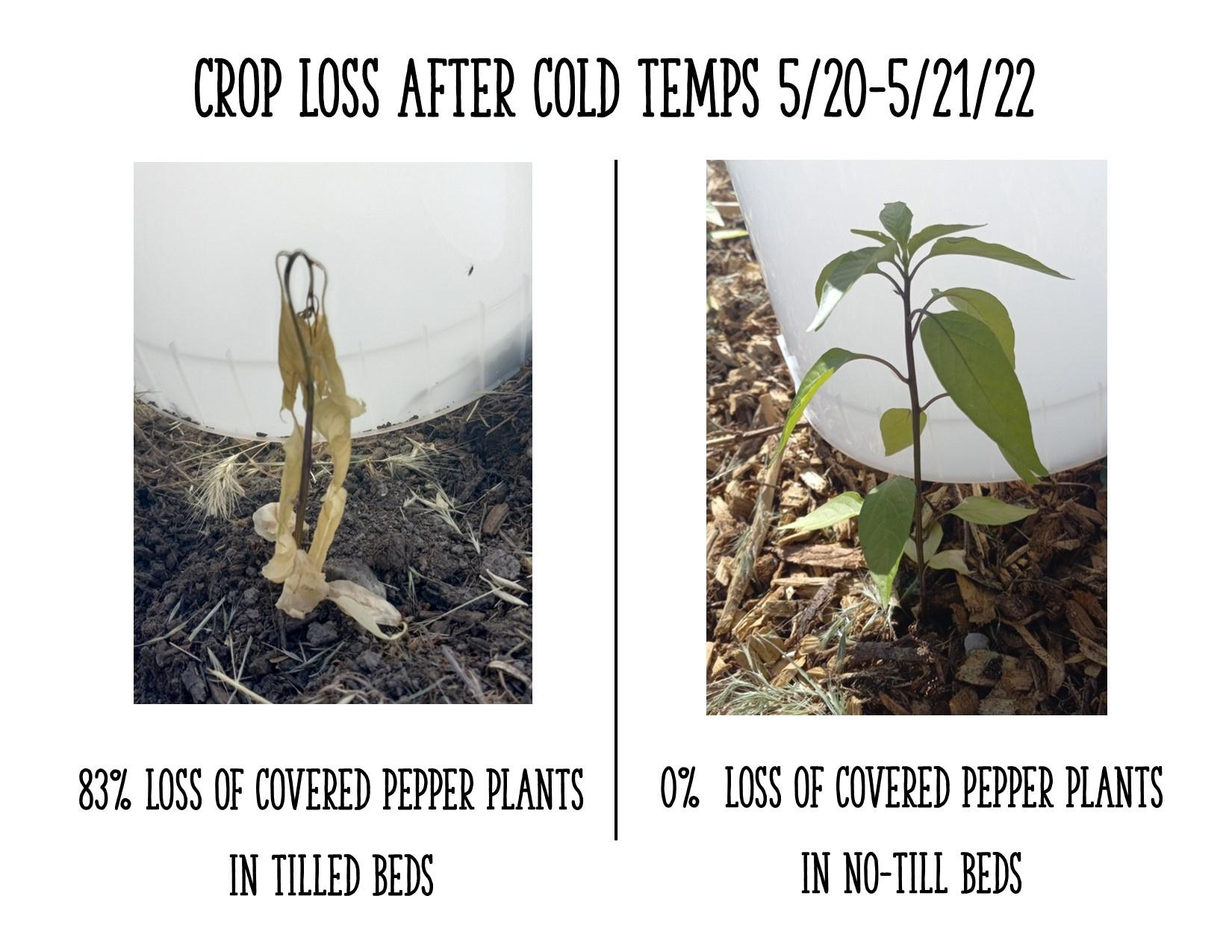

Tilling is the act of physically churning the soil, usually done with the intention of preparing new ground for cultivation, aerating the soil, or clearing weeds. While it can provide some instant gratification for some of these goals, its long-term effects are very damaging to fungi. Mycorrhizal fungi are obligate symbionts, meaning they cannot live without an attachment to plant roots. When we till our plants, we kill our plants and our fungi. This means we no longer have AMF, which halts the production of glomalin, and ultimately leads to low quality, compacted soil. To compensate for this, we then add excessive fertilizers which often end up in rivers and lakes causing eutrophication (excessive nutrients that harm aquatic life).

Monocropping is the practice of planting one crop over large areas of land. This limits the type of soil biology that will grow there and leaves the crop susceptible to disease. Intercropping a variety of plants facilitates fungal diversity and puts your cultivated ecosystem in a better position to fight off disease and pests.

Fungicides, even copper fungicides approved for organic agriculture, tend to kill a wide range of fungi outside of their target. If we are facilitating healthy soil biology, we shouldn’t need fungicides.

How can we take care of our soil fungi?

The first step towards improving soil fungi is to change your mindset from focusing on the plants to focusing on the soil. If we nurture the soil, the soil will then nurture the crops.

An important thing to remember is that improving fungal growth takes time. There aren’t any quick fixes, so patience is key!

There are a few key ways that we can start supporting fungi in our gardens:

- Transition to a no-till system

- Think about what you’re adding to your garden

- Think about what you’re planting and where